A Guide to Assam Teas

Assam is probably the most famous black tea producing region in the world. It is the single largest black tea producing region in the world. The story goes that the British discovered wild tea plants growing in Assam, what came to be identified as a new species, the Camellia sinensis var. Assamica. The Assamica leaves are larger than the Chinese species of the same tea plant. The differences go beyond just that, to the flavours each produce. Assam teas are malty with a distinctive aroma.

Tea Regions of Assam

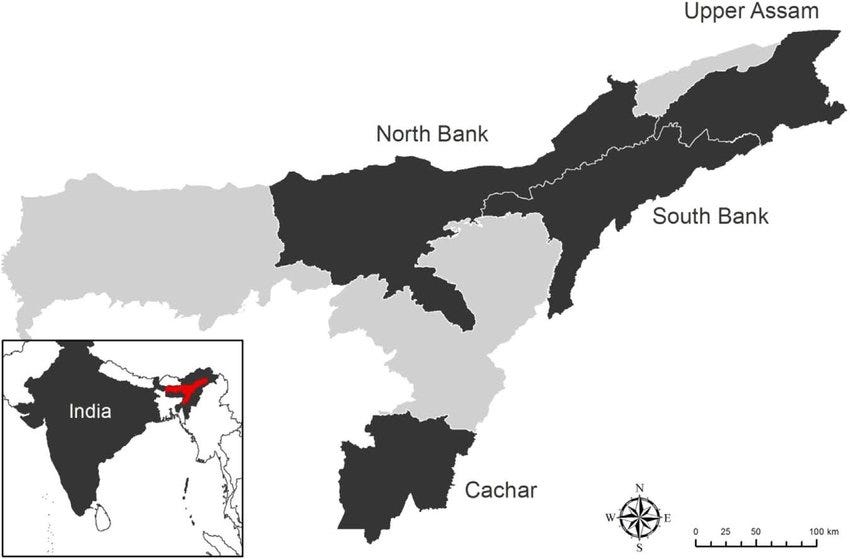

But first, a brief geography lesson. Assam is an Indian state in the northeastern part of India. Bordered by the rest of the far eastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram and West Bengal, Assam also shares a border with the countries of Bhutan and Bangladesh. The Brahmaputra flows from Tibet into Arunachal Pradesh and further down through the breadth of Assam, creating a very fertile valley.

Assam has four main tea growing regions.

- Upper Assam which makes up the districts of Dibrugarh, Jorhat, Sibsagar and Tinsukia,

- Barak Valley, which includes Cachar.

- North Bank is districts to the north of the Brahmaputra, and

- South Bank to its south.

Harvest Seasons

In Assam, tea is harvested from March to November. Four distinct harvest seasons, made up of growth periods called a “flush”, with resting/dormant periods between flushes, called the “bhanji”. In winter, December to February, the tea gardens are closed for pruning and maintenance. While every season presents its unique teas, the most famous are the ones produced in spring called the “second flush”. In late autumn, we get another quality period. These two flushes display the characteristic flavours of Assam’s black teas at its best.

First Flush: The first flush in Assam is a relatively short season that starts with a few showers, usually in early March. With changing environmental factors, in the last decade and a half, this season has not been significant in production and ends in an intermediate dormancy period that we call bhanji. The first flush tea is bolder, showing more body but lacks the quality we see in the second flush. If you like your morning cuppa’s to be bold and robust, first flush teas are for you.

Second Flush: The second flush is our spring harvest and takes place just before the monsoons arrive in Assam. The unique quality characters of Assam tea, i.e., the maltiness, briskness, seasonal flowery, sweet and fruity flavours are the attributes of the tea bush coming out with vigour after the long dormancy rest.

The bhanji period that occurs after every flush/season with the one before the second flush being the longest at three weeks. This dormancy allows the bushes to rest and offer better quality leaves at harvest. The shoots will be yellowish, covered with fine hairs (pubescent/puberulent) which will be most prominent — all symbolic indicators of quality in the tea shoots.

Teas made in this period often get the best prices at the tea auctions, each year, and make for a lovely afternoon cuppa.

Rain flush: The second flush progresses until the monsoon arrives, usually mid-June. A short bhanji period gives way to the rains flush. In the rains, we don’t see the best quality of tea as water in the shoot produces a lighter liquor. As nature would have it, the rain flush is the longest and most productive because the tea bush thrives in the heat and humidity of Assam. In a good year, this flush will contribute to a third of a tea farm’s annual production.

Autumn flush: The rains retreat with the onset of autumn, bringing another short bhanji period. We look forward to the winter, when temperatures dip to a pleasant 10–15 degree Celsius. This harvest is short, going up to the first week of December. At Aideobarie, with the help of Amarnath Jha, our tea master, we have begun to make some delicious white and green teas at this time. These teas are sweet, mellow and intensely fruity.

After the autumn harvest, complete dormancy sets in — growth of tea shoots stops for the remainder of the winter season. We use this time for the upkeep of land and plants; bushes are pruned and skiffed, and the farm machinery is overhauled and made ready for the new season.

Production styles

There are two distinct production styles in Assam — the whole leaf “Orthodox” style and the “CTC” style, or Crush-Tear-Curl. Tea factories in Assam predominantly produce CTC tea for the wholesale commodity market.

World over, people favour Assam Orthodox tea for the quality offered by its production style. The intent is to maintain the integrity of the leaf, and therefore the original flavour profiles.

In the 1950s, the industrial revolution brought in modern machinery and allowed the introduction of the CTC style. Growing tea on large plantations, and manufacturing CTC tea with faster machines became a reality. The output was a homogenous, pellet-like tea. The industry chose to trade in flavour for efficiency. Volume of production and strength of cup won. CTC is the tea of choice for Chai in India, where cup-strength is favoured, with enhanced flavours through added spices and sugar. Addition of milk brings down any astringency that the tea itself may add to the cup.

A few tea farms like Aideobarie continue to manufacture the Orthodox variety, which was the authentic way of making tea for the first 120 years of the industry’s existence in Assam. For those who like the flavours to be front and centre to the cup, Orthodox tea is preferred.

Tea Grades

Traders introduced the grading system for the express purpose of acting as standard indicators at the auctions; where the grade is an indicator of leaf size, the price point and strength of cup in a given season, albeit with uniqueness from a growing region. Once tea is dried and ready, sorting follows, making the different grades.

Whole Leaf: These are amongst the best teas, where the tea leaf retains its integrity. It indicates a high standard of plucking, i.e. a shorter harvesting round. Usually the harvesting round within a flush is seven days. For more delicate teas, it is even quicker — three to four days. The careful withering of the leaves to achieve the right chemical reactions required is next in importance, if the highest flavour profiles in the tea are to be attained. All the steps in the process are important, but the quality of the green leaf plucking and the withering of the green leaf, are by far the most important. Whole leaf teas are Orange Pekoe (OP), Flowery Orange Pekoe (FOP) and higher, all the way up to Super Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe (SFTGFOP).

Broken Leaf: If the withering weren’t up to standard, the leaves would break into smaller parts, during the rolling process, which follows. The flavours, which are volatile compounds, escape in this process, rendering the tea a little less flavourful than the whole leaf grades. The abbreviations B is used to denote a broken leaf grade, and are graded BP (Broken Pekoe) and higher, up to Tippy Golden Flowery Broken Orange Pekoe 1 (or TGFBOP1).

Fannings: These are usually the flaky stalk of the tea shoot, and recognisable as the fine tea particles. They are what remains after separating the whole leaf and broken leaves. Fannings are chosen for tea bags because they infuse quickly and make a strong cuppa. Not entirely what you would have expected in a teabag.

CTC: A grading system also measures the CTC teas. There are CTC tea grades that produce some delicious cups. The CTC tea is well suited to someone who enjoys a strong tea made with milk. Here, at Rujani, we enjoy an unsorted tea, what we call a “Dryer Mouth CTC”. This unsorted tea holds all the grades from the largeish BOP (Broken Orange Pekoe) to the fine Dust (D), making for a well rounded and balanced cup of tea with milk.

Dust: Dust grades are Pekoe Dust (PD,) Dust (D) and Chirumoni Dust (CD). These CTC grades have a tiny particle size, and they give more ‘cuppage’. You get roughly 400 cups per kilo from dust teas, versus around 250 cups from the CTC grades such as BOP, BOPSM and BP. Dust grades are a popular choice for use in restaurants and the hospitality sector as they offer better commercial return. Dust grades also give a more robust (karak in Hindi) cup of Chai. This tea grade is very popular in South India.

How to choose an Assam black tea?

At Rujani, we are championing the whole leaf Assam tea. You will find that the shoot in most of our pure whole leaf tea remains intact all right till you make your cup of tea. How we wither and roll the supple tea shoots is the difference; most of the rolling is done by hand and in very small batches.

Among Assam teas, the most select teas are those that have an abundance of gold and silver tips, the tippy teas. Careful plucking of the tips or unopened shoots/buds and withering thereof, are essential. The tips contain the highest proportion of the compounds that bring flavour to a cup. One of our favourite teas is our award-winning, flavourful Tippy Reserve, made by keeping the shoots intact. We also recommend a whole leaf orthodox grade like the Assamica Premium, made from STGFOP1 Clonal. The ‘clonal’ in any whole-leaf grade indicates that it will be a ‘tippy’ tea made from select tea cultivars.

A handy guide to the Rujani whole leaf Assam teas

If you enjoy breakfast teas, like an English or Irish Breakfast, choose our Premium Orthodox or Morning Special.

If your preference is for Chai, choose our Royale Golden CTC.

If you are a fan of the Earl Grey, we have an Assam whole leaf Earl Grey blended with organic bergamot oil and blue cornflower.

If you have never tried an Assam whole leaf tea before, we recommend that you try our Rujani Muscatel. This tea embodies the best of Assam, in a flavourful cup.

If you like a slightly smoky black tea, like a Lapsang Souchong or the Russian Caravan, our Smoky Ecstasy is a tea we recommend.

Learn more about our speciality teas online on our website.

Enjoy your cuppa!